Robert Moses - The Most Important Person You've Never Heard Of

Article Table of Contents

- A review for The Power Broker.

- An Interview with Robert Caro

- A Sense of Scale - The Cross-Bronx Expressway

- Chapter 36: The Meat Ax

- Gowanus

- Misc Related Resources

- Various shorter-than-the-book resources

- Appreciate the kind of person that could be responsible for the Henry Hudson Parkway

- Footnotes

this was originally posted a few years ago, republishing as a blog post as I organize an increasingly large number of links and resources here.

Here’s a big dumping ground for some resources on robert moses I’ve got floating around.

Obviously, this has grown to an unwieldy sizy and less would be asked of you if I organized it a bit better.

Here’s some starting points, to start conceptualizing his reach and influence, and to start appreciating how he obviously set systems up around himself, and people, which faithfully reproduced his very specific way of being into the world around him.

What is currently underappreciated, in the narrative of Robert Moses, is a point that I feel like I can maybe express semi-concisely now, but has been coalescing in my mind for a while. There’s a few potential kinds of poeple that might find themselves reading this, so I’ll state the same concept at least twice, or have to define some terms, before feeling like I’ve landed it. Relates to appreciating phenomina that are operating today, tightly linked to recent history.

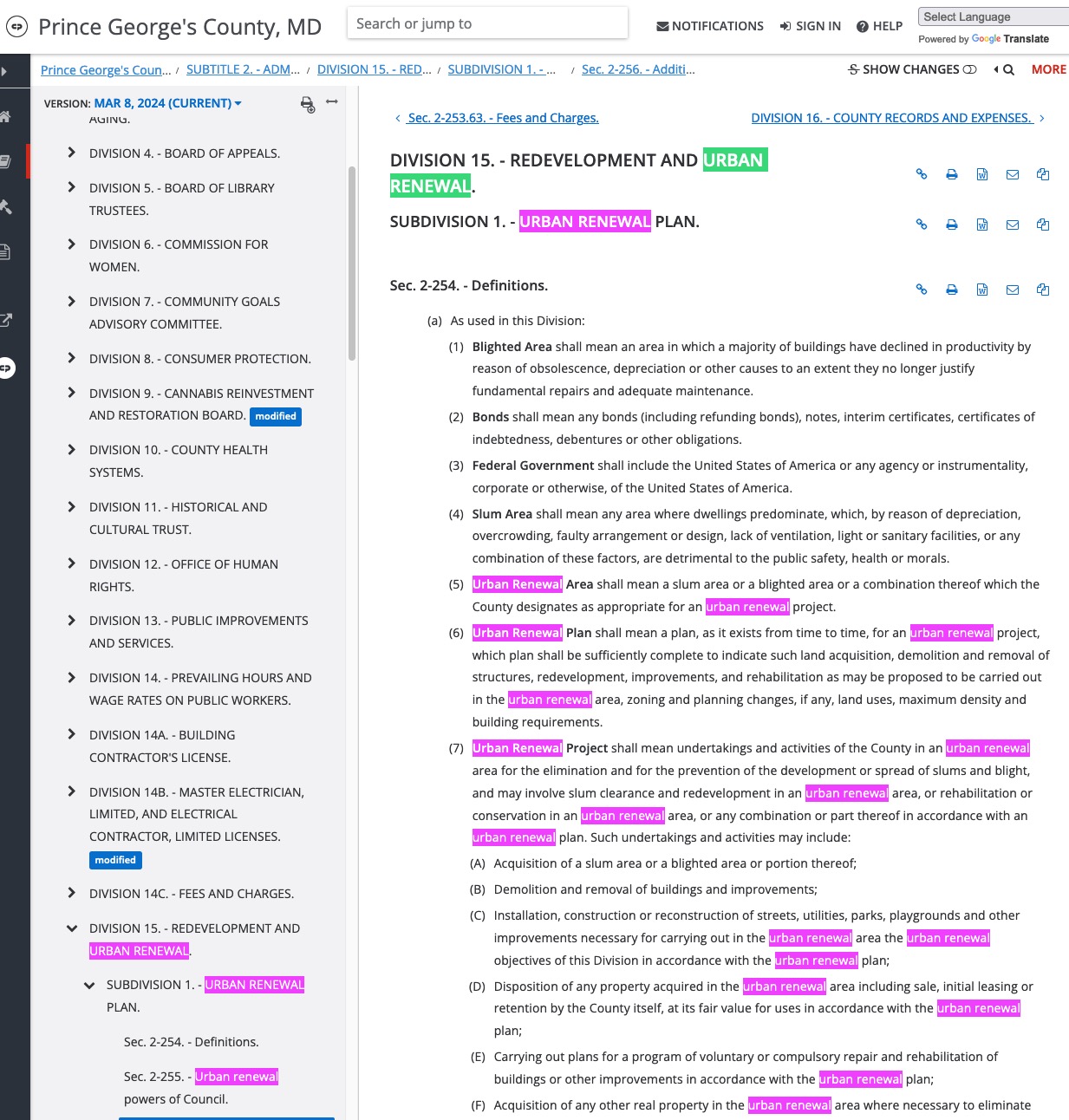

- “Urban Renewal” is a real, namable, visible process that is plainly visible within every single american city. Not only are the evidences of it clear, but the evidence is not hidden. Nearly every american municipality has a body named “{LOCAL JURISDICTION} Renewal Authority”. Various similar titles are “Urban Renewal Authority”. There is both a Golden Urban Renewal Authority (still running today) and a Denver Urban Renewal Authority. Prior to Colorado, I lived in Maryland. Here’s Montgomery County ‘office of planning and development’ ‘redevelopment and revitalization efforts’. [^urban_renewal] More of the same for Prince George’s County, MD:

-

“Urban Renewal” is a propagandistic phrase, those who were getting it done to them understood it to be a cleansing, a displacement, a relocation. All/enough parties understood it to be what it was. The people experiencing the ‘renewal’ understood it to be what it really was - cleansing. It involves efforts of one group to define, confine, and relocate, persons that can be ‘pushed’ into another group.

-

Urban Renewal is virtually synonymous with ethnic cleansing, and needs to be treated as such. The Slaughter of Cities: Urban Renewal As Ethnic Cleansing

-

Robert Moses invented the social tool “urban renewal” as his “title 1” powers. He created systems around himself to duplicate his own thinking into the world around him. His was the godfather of the Federal Highway Administration, and pioneered ‘innovative’ ways municipal governments could work with federal governments, and how various parties could ‘drive stakes’ and ‘whipsaw’ political interests into whatever one wanted.

To appreciate Robert Moses and to appreciate the scale of the urban renewal programs (always aimed at maintaining the supremacy of some) is to both want to die at the scale of devestation, to weep over the ongoing harm this causes everyone today, and will cause tomorrow, and it’s to appreciate a way out, perhaps. A post-robert-moses world.

God, I want to get there, out of his world. Highways? Parkways? Signal-controlled intersections? controlled-access highways? setbacks? residential zoning and commercial zoning and strip mall zoning? Parking minimums? General Motors and Ford? Robert. Bobby Moses. RM. Its your boy.

(When you read the book, you’ll learn that when we was doing all these things for NYC, the country was so small that whatever NYC did eventually everyone else wanted to do the same. sorta still the same. RM was synonymous with “NYC infrastructure” and, in fact, New York infrastructure and beyond. HIS dam, the Robert Moses Power Dam, is the dam of niagra falls. 😳)

<photo from powerbroker index, ‘urban renewal’, ‘title 1’>

A review for The Power Broker. #

In a moment, I’m going to quote extensively from a book review left on the Goodreads listing for The Power Broker. Here’s a link to the review itself, directly, if you’d like.

I will never be able to write as well as this reviewer, and I believe so much of what they say so accurately conveys some of the experiences I had, so I’m quoting it in full below. I’ll add linebreaks, and emphasize some sections:

[The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York by Robert Caro] is definitely the greatest book that I have ever read.

Midway through adolescence, I began wondering a bit which life event would finally make me feel like an adult. Of course I had the usual teenaged hypotheses, and acted accordingly to test some of them out. Getting drunk? Having sex? Driving a car? Going to college? None of these things did make me feel grownup; in many instances, their effect was the opposite.

I had a brief thrilling moment of maturity when I voted for the first time at age eighteen, but election returns in the years since (in particular the 2004 presidential race) dulled the sophisticated glamour of the ballot box, forcing me to admit that an ability to vote does not indicate the presence of intellectual maturity…

The first time I got a job with benefits and sat through a presentation explaining the HMO plan, life insurance, and “401K,” I did feel old in a certain kind of way, but there was a sense of the absurd to it, as if I were in drag as an adult, staggering around in my mother’s too-big high heels and smudgy lipstick in a silly effort to look like a grown woman.

For the past few years I’ve had the sense of wearing an oversized grownup life that wasn’t actually mine, while that magical rite of passage into adulthood continued to elude me. Maybe when I have children things will click into place, I’ve mused, listening to Talking Heads with one ear and sort of doubting it…. Part of this might be generational; if thirty is the new twenty, it’s no wonder that I get that Lost Boys feeling, and shrug confusedly when overnight company makes fun of my teddy bear.

I’m pleased to announce that thanks to the glory of Robert Caro, this stage is basically behind me. Having finally finished The Power Broker, I feel much more like a grownup, and believe it or not, I’m pretty into that.

When I was a little kid, I felt that the adults around me had a thick, rich, complicated understanding of the way the world worked. They knew things – facts, history – and they understood processes and people and the way something like a bond measure or a public authority worked. It was this understanding – which they had, and I didn’t – that made me a child, and them adults. Grownups had an infrastructure of information, truth, and insight that I lacked.

As I grew older, I was dismayed to discover that grownups really didn’t know a fraction of what I gave them credit for, and that most of the people ostensibly running the world had no clue how it operated, and my intense disillusionment caused me to lose sight of that adulthood theory for awhile.

But reading this book made me feel like a grownup because it helped me to understand the way the world works as I never had before.

This book is about power. It is about politics. It is a history of New York City and New York State. It is an explanation of how public works projects are built. It is about money: public money, private money, and the vast and nasty grey areas where they overlap. This book is about democracy, and the lack thereof. It is about social policy, and economics, and our government, and the press. This book is about urban planning, housing, transportation, and about how a few individuals’ decisions can affect the lives of the masses. It helped explain traffic in the park, and the projects in Brownsville, and a billion other mysteries of New York City life that I’d wondered about.

The Power Broker is about ideals, talent, and institutional racism. It is about inequality. It is about genius. It is about hubris. It is the best goddamn book I have ever read in my entire life, hands down, seriously.

Please do not think that it took me five months to read this book because it was dense or slow! This was a savoring, rather than a trudging, situation. Robert Caro is an incredibly engaging writer. One thing that happened to me early on from reading this was that I lost my taste for trashy celebrity gossip. Who CARES about Britney’s breakdown or, for that matter, Spitzer’s prostitute peccadilloes when I could be reading about the shocking intricacies of Robert Moses’ 1925 legislative consolidation and reorganization of New York State’s administrative structure?

This book gave me chills – CHILLS! – on nearly every page with descriptions of arcane political maneuvering and fiscal policy so riveting that I lost my previous interest in reading about sex and drugs. Let’s face it: sex and drugs are pretty boring. Political graft, mechanics of influence, the workings of government: now that’s the hot stuff, when it’s presented in an accessible and digestible form. Nothing in the world is more fascinating than power, and Robert Caro writes about power better than anyone I’ve come across. There are no dry chapters in this book; there’s barely a dull page. It is infinitely more readable than Us Magazine, and not much more difficult.

Of course The Power Broker is many things, among them a biography. While any one portrait of New York power icons from Al Smith to Nelson Rockefeller is more than worth the price of admission, this book is primarily about Robert Moses. Caro understands and explains the relationship between individual personalities and systems. One of his main theses is that Moses achieved the unchecked and unparalleled levels of power he did because he figured out how to reshape or create systems around himself. The Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority would not have existed without Robert Moses, and Robert Moses would not have been what he was, or accomplished what he did, without the brilliance he had for shaping the very structure of government into conduits for his own purposes. To explain this, Caro needs to convey a profound understanding not only of how these systems worked, but of who this man was. He does so, and the result goes beyond Shakespearean: it is Epic. The Power Broker is the story George Lucas was trying to tell about Anakin Skywalker’s transformation to Darth Vader, only George Lucas is no Robert Caro, and The Power Broker succeeds wildly in the places where Star Wars was just a hack job (of course, Caro wasn’t handicapped by Hadyn Christensen, which does indirectly raise the burning question: WHO’S OPTIONED THIS???).

Robert Moses was an incredible genius. He was also an incredible asshole. Robert Moses was probably one of the biggest assholes who ever lived, or at least, who ever got free reign to redesign a major modern American city to his fancy. One of the innumerable triumphs of this book is that while it certainly does demonize Moses to a great extent, it doesn’t seem to do so unjustifiably, and it never strips him of his humanity. Caro conveys a deep respect and empathy for his brilliant subject, even as he also expresses horror, disgust, and rage as he describes Moses’ forty-four-year unelected reign of power.

I know it’s a mistake to do this review right after finishing, and I’m a bit grossed out that I could write something so gushingly uncritical; that’s unlike me, and it’s possible that later I’ll think of some complaints… I might not, though. I really do think that this is the best book I’ve ever read, and I wish there were some way that I could adopt Robert and Ina Caro as my grandparents, and that I could go over to their house for Sunday dinner and then take walks together in Central Park. Right at this moment I believe that Robert Caro is the smartest person in the world, and I’m not in the least bit resentful that I’m going to have to devote the rest of my life to reading his LBJ doorstoppers; in fact, I welcome it (though I’m not in a huge hurry to start).

Oh, I’m sure this book has flaws like any other. My main problem with it was that it was too short. Caro did not go into nearly enough detail about a large number of issues that I’d expected to learn about. For instance, there was little more than offhand mentions of Moses’ upstate projects; I was surprised that there was virtually nothing in here about Niagara Falls. There was also almost nothing on Shea Stadium, and while they did keep coming up, I never felt adequately informed about Moses’ plans for the three crosstown expressways, and the successful opposition to them. How real a prospect were these, and what did the public fight look like? I wasn’t so clear on that. While it’s possible that Caro had nothing interesting to say about these projects, it’s more likely that he had to draw the line somewhere, and 1162 pages was that place. I mean, otherwise he probably could’ve gone on forever…. There’s a lot to say.

I definitely recommend that anyone who reads this book do as I did, and divide it with an exacto knife into four duct-tape bound commuter volumes. It’s fun to draw your own Power Broker covers on your personalized editions, and a good excuse to pull out those crayons which, as a bona fide adult, you so rarely use!

It occurs to me that I’ve babbled on forever but still haven’t explained at all what this book is about. If you think you might want to read it but you’re not sure, check out this article by Robert Caro: Robert Moses: The Man Who Built New York

It has those stupid New Yorker dots, which the book thankfully does not, but otherwise is kind of like a miniaturized version of The Power Broker and gives a much better sense than I just did of what it’s all about.

An Interview with Robert Caro #

Here’s a 1h45m Audible “short” with Robert Caro, the man who wrote The Power Broker

On Power, by Robert Caro (Audible)

Here’s the audible summary:

From two-time Pulitzer Prize winner and two-time National Book Award winner Robert A. Caro: a short, penetrating reflection on the evolution and workings of political power - for good and for ill.

In On Power, an Audible exclusive, the legendary historian Robert A. Caro reflects on what drew him as a young journalist to study political power and what his half century of reporting on New York City urban planner Robert Moses and President Lyndon Johnson has taught him about the inner workings of government and democracy.

Adapted by the author from two recent speeches and filled with thoughtful lessons and personal moments, On Power goes behind the scenes in the author’s decades-long quest to understand how power works, often in ways he could have never imagined.

Listening to On Power, narrated with emotion and humor by Caro in his unmistakable New York accent, is like having a private audience with the author often hailed as our greatest living historian. Longtime fans of Caro’s books, as well as those seeking a more personal introduction to his life and work, will be treated to his trademark wit and revelatory insight.

But more than anything, On Power is a timely reminder for those who want to better understand how power and government work.

In Caro’s words:

Why political power? Because it shapes all of our lives. It shapes your life in ways that you might never think about. Every time a young man goes to college on a federal education bill passed by Lyndon Johnson, that’s political power. And so is a young man dying in Vietnam. Every time an elderly person is able to afford an MRI, that’s Medicare. That’s political power. It affects your life in all sorts of ways. My books are an attempt to explain this power…. Because the more America understands about political power, the better informed our votes will be, and then, hopefully, the better our democracy should be.

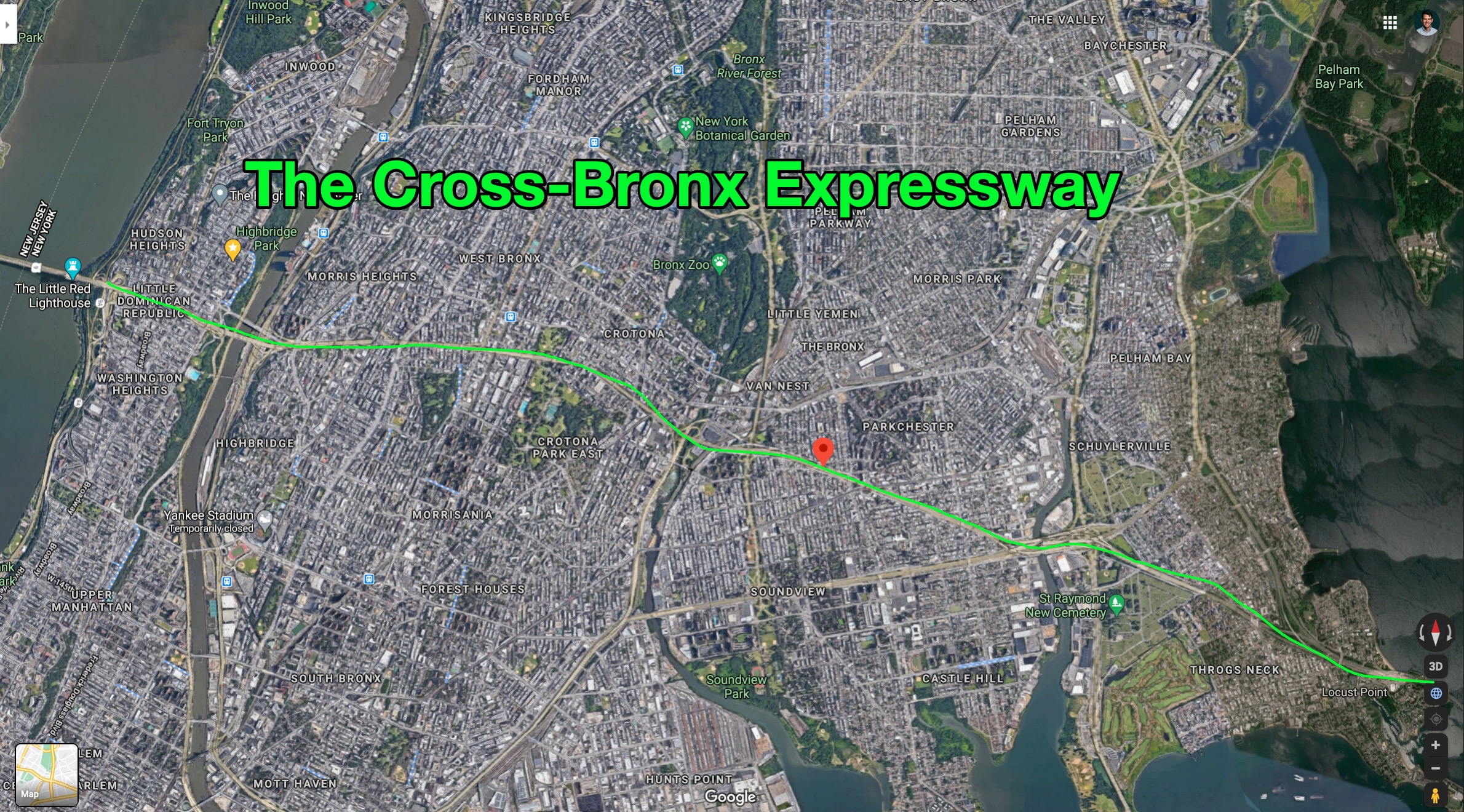

A Sense of Scale - The Cross-Bronx Expressway #

What do you think of when someone says “The Bronx”?

Everything you think about The Bronx, and indeed New York City, and the weight NYC has had on global culture is shaped by Robert Moses.

From Robert Moses and the Cross-Bronx Expressway

Here’s the Cross-Bronx Expressway:

Another view of it: It crosses that elevated bridge on the right, and continues to the bottom left of the picture:

What do you think it looked like to cleave such a deep cut through a heavily built-up area?

Robert Moses was considered the most “powerful modern builder of all time”. He was know especially for the building of the Cross-Bronx Expressway.

This highway connected New Jersey, North Manhattan, South Bronx and ended up in in Long Island through wither either the Throgs-Neck Bridge or the Whitestone Bridge. The building of this new highway system meant that over 60,000 residents would have to be uprooted and relocated to new areas. Most of these people lived in South Bronx. Moses led the white exodus out of the Bronx. Most of the white residents moved to either Westchester or Northern Bronx areas and others moved to small suburban houses being built around the Cross Bronx Expressway in New Jersey.

The poorer residents who where given a meager $200 per room compensation were forced to move out and settle in new high-rise apartment buildings that were being built. These new behemoths had could include up to 1700 apartments per building.

As a result of this mass relocation the economy of the Bronx suffered immensely. The South Bronx area (mostly Black and Puerto Rican) lost over 600,000 manufacturing jobs. Youth unemployment rose to 40 percent and in some areas as high as 80 percent.

The most devastating affect of the Cross Bronx Expressway took place when the newly built apartment buildings passed into the hands of slumlords. These people used many different tactics such as demanding more money when they shut off heat and water supply to the tenants.

Another tactic that the slumlords used proved to be the most effective and profitable for them. They would find junkies and rent-a-thugs to set fire to abandoned apartments and then they would collect the insurance polices from the city. The slumlords profited greatly from this enterprise as they collected as much as 150,000 dollars per fire. The insurance companies didn’t really mind in the begging as they were leasing out many new insurance policies, but after a time even they realized that their costs were beginning to get to high.

In the end as insurance companies refused to provide insurance policies to cover certain buildings in South Bronx and the fires continued to spread, whole city blocks became completely abandoned and opened up a place for crime and gangs to fill the void.

Chapter 36: The Meat Ax #

I’m copy/pasting the summary of Chapter 36: The Meat Ax from somuchtoread. That website doesn’t have deep-linking to the page, so it’s easier to stash notes here:

Chapter 36: The Meat Ax

Caro is firing on all cylinders now, and it turns out that “The Meat Ax” is how he describes Moses’ approach to building roads. In a way, this chapter is an introduction to the following two brilliant chapters, “One Mile” and “One Mile: Afterward.” The title of the chapter is referring to how Moses once described the challenge of building in “an overbuilt metropolis,” noting the only way to achieve success is to “hack your way with a meat ax.” This is horrifying language to Caro and he intends to show how Moses’ meat ax destroyed homes and families and neighborhoods.

Caro writes that “it is no accident that most of the world’s great roads–ancient and modern alike–had been associated with totalitarian regimes.” The reference is obvious to anyone who has read 846 pages of this book. Moses, “had a dictator’s powers”, and was able to cut and carve up communities to work his will on the people because of his power. He, like others in command of a totalitarian regime, was able to make a decision because his mind, and his mind alone, had been persuaded.

The title of this section of the book is “The Lust for Power,” and this chapter fits nicely into that theme. Caro points out that Moses enjoyed working his will on a neighborhood–“he loved to swing [the meat ax].” It’s a damning charge: Moses isn’t someone who wants to build a project because the project itself is good, he wants to build the project because it strengthens his own power and feeds his own ego.

At times, I’m still in awe of Moses. Believe me, Caro makes it tough to like the guy. But he is pressing forward and paying attention to infrastructure. Neighborhood groups be damned. In the Cincinnati bridge example we’ve already considered, a true Moses-like figure would run roughshod over the buildings and houses in Covington that are adding money and time and opposition to the project. Our inability to be like Moses is delaying by years a bridge that is imperative. Moses always claimed that “succeeding generations would be grateful.” What are we going to say generations from now if we never build that bridge because we’re worried about a few houses? Wouldn’t we be grateful if we had our Moses once in a while?

I guess it depends on whether you live in those houses or not. So much to think about with this book.

Gowanus #

Gowanus is a neighborhood that is featured in The Power Broker, as an example of how Robert Moses would use highways to destroy neighborhoods.

I’ve listened to the Nice White Parents podcast series, which I remember ending, then “the next episode” the host was like “wow y’all after I finished up reporting this crazy cycle started up again and I watched in rapt awe as it played out again lets follow along”.

I wasn’t surprised, because I’d read The Power Broker and followed along in rapt fascination. She basically expressed shock watching the effects of de facto segregation playing out, again.

de facto segregation, not de jure1

Anyway, it was the ‘school of international studies’ for a time. The school in Nice White Parents.

From a great story about Robert Moses:

The construction of the Gowanus Parkway, laying a concrete slab on top of lively, bustling Third Avenue, buried the avenue in shadow, and when the parkway was completed, the avenue was cast forever into darkness, and gloom, and its bustle and life were forever gone.

And through that shadow, down on the ten-lane surface road beneath the parkway, rumbled (from before dawn until after dark after the opening of Brooklyn–Battery Tunnel flooded the area with freight traffic) regiments, brigades, divisions of huge tractor-trailer trucks, engines gunning and backfiring, horns blasting, brakes screeching, so that a tape recording of Third Avenue at midday could have been used as the soundtrack for a movie of a George Patton tank column.

And from above, from the parkway itself, came the continual surging, dull, surf-like roar, punctuated, of course, by more backfires and blasts and screeches, of the cars passing overhead.

Once Third Avenue had been friendly. Now it was frightening. (…) Once the avenue had been a place for people; Robert Moses had made it a place for cars.

Denver, Colorado, has it’s own version of Gowanus and the International School like the Nice White Parents pod, the Denver Center for International Studies. It’s right next to a HUGE 5-line one-way insanely bad road.

Everything around me is ruled by the systems Robert Moses set up. It hurts to behold.

Misc Related Resources #

- Twitter convo between me and Matt Swanson about this book

- Robert Moses and re-making the political machine (substack)

- Chapter-by-chapter summary of The Power Broker

- somuchtoread.com section-by-section read-through (original site broke, now links to wayback machine copy). Follow the link, scroll down the website to the author’s summations of

Chapters 37 and 38: One Mile and One Mile Afterward. Or the section on the chapter “The Meat Ax”, ch 36. - Beware of the Robert Moses Revisionists

- The City-Shaper (by Robert Caro!)

- Robert Moses and the Cross-Bronx Expressway

- The Power Broker by Robert Caro: Summary & Notes

- The Power Broker notes (nateliason.com)

- In the Footsteps of Robert Moses: Roadtripping across the bridges, highways, and parks of America’s most controversial urban planner

- The History of Denver’s Streetcars and Their Routes Robert Moses hated the kinds of people who used street cars and trains for travel, so he hated their trains, easily managed to run the train companies out of business. Look at what Denver could have had, but for Robert Moses and supremacy thinking. The reason Denver is currently a car-dominated hell-hole is… Robert Moses.

Various shorter-than-the-book resources #

👉 22 minute modern documentary about Robert Moses on Youtube

👉 a 25 minute ‘comedy show’, episode titled “I Won’t Go”, youtube about an entire municipality and police force evicting an old lady from her house, and her various ways of trying to remain in her own house. Episode ends with her pointing out to everyone where her house used to be, under what was then turned into an approach road for one of Robert Moses’ bridges.

👉 Motherless Brooklyn, 2019 movie/crime-drama, features the devastation experienced in a certain neighborhood experiencing Robert Moses-inspired ethnic cleansing. It was originally a book, Edward Norton turned it into a movie, and he also played a leading role. I didn’t realize he was obsessed with The Power Broker - I sorta stumbled into the movie, and was shocked when I realized the opening scene of the movie is the exact same as the opening scene of The Power Broker. (wikipedia). The rest of the movie is excellent, even if only to appreciate yet another lense through which Robert Moses’ influence was being experienced.

👉 1-hour Vimeo documentary about Robert Moses #

I just found this link. It’s the first time I’ve seen so much footage of Moses himself talking, and his acolytes talking about him.

THE WORLD THAT MOSES BUILT (vimeo)

The reflexive love so many people had of his high modernism/authoritarianism/supremacy is on full display.

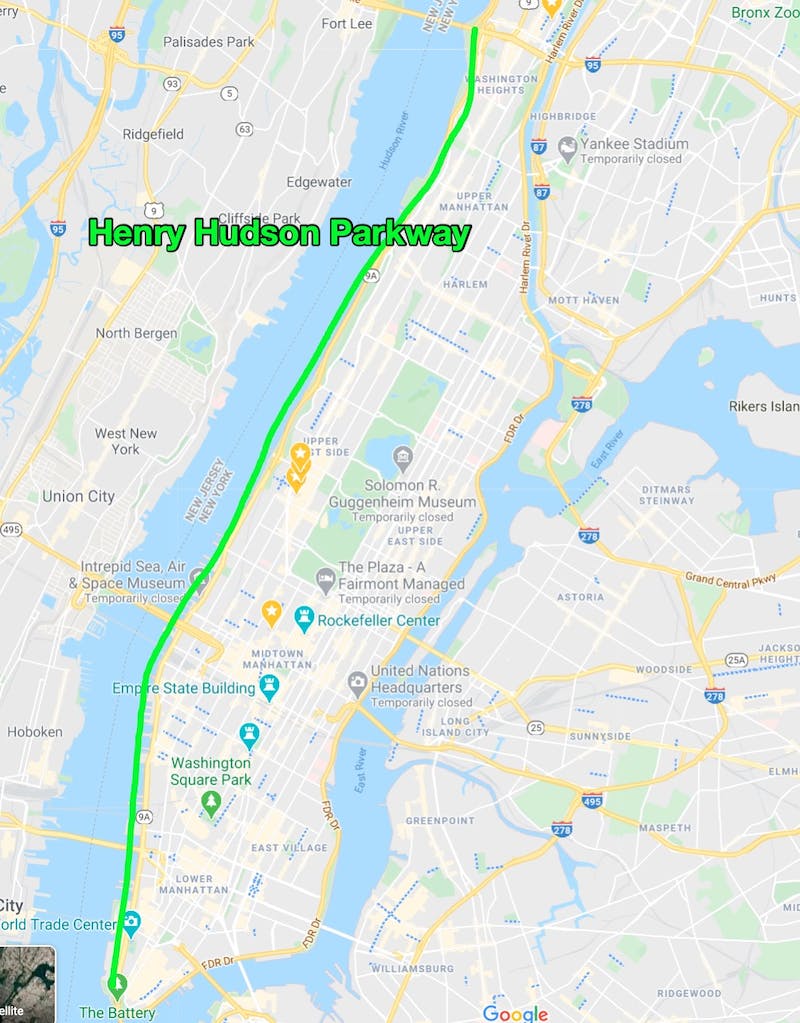

Appreciate the kind of person that could be responsible for the Henry Hudson Parkway #

The person single handily responsible for building that highway is powerful indeed. This person built many other highways, and displaced about 250,000 people, almost completely comprised of ethnic groups Moses considered undesirable.

Read what is said about the author of Robert Moses’ incredible biography:

As a reporter for Newsday in the early 1960s, Caro wrote a long series about why a proposed bridge across Long Island Sound from Rye to Oyster Bay, championed by Robert Moses, would have been inadvisable. It would have required piers so large as to disrupt tidal flows in the sound, among other problems. Caro believed that his work had influenced even the state’s powerful governor Nelson Rockefeller to reconsider the idea, until he saw the state’s Assembly vote overwhelmingly to pass a preliminary measure for the bridge.

“That was one of the transformational moments of my life,” Caro said years later. It led him to think about Moses for the first time. “I got in the car and drove home to Long Island, and I kept thinking to myself: ‘Everything you’ve been doing is baloney. You’ve been writing under the belief that power in a democracy comes from the ballot box. But here’s a guy who has never been elected to anything, who has enough power to turn the entire state around, and you don’t have the slightest idea how he got it.’”

This biography is long. If you’re like me and you’re thrilled to find a long book that you’ll love, you’ll be happy to know his biography is almost as long as all of the harry potter book series.

Footnotes #

-

old legal texts like to use magical words with special meaning. “de facto” means “the express written goal of the act” while “de jure” means “it just sorta happened as a byproduct”, and some of the ‘american narrative’ relies on structural support from the projection that ‘segregation’ was a ‘byproduct’ of something else going on at the time. ‘de facto’ means ‘nope, the thing you’re calling

byproduct segregationwas actually the point and everyone at the time knew it’.The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America gets into it more. ↩