Hey there. Did you get to this page because I (Josh) sent you the URL?

Great! Welcome. This is a page I share infrequently, and it’s not linked from anywhere else on this website.

Read on. If you decide you want to keep chatting about this with me, there’s a form at the bottom for a small email list. There’s less than 10 people on it.

Below are the first ten sentances of a book that I’ve read.

I want to know if they strike you the same as they strike me.

J. Denny Weaver, an anabaptist scholar, wrote the book, and William H. Willimon, a Methodist bishop, wrote the forward. Prior

After you read the these sentances, I’ll provide a bit more context.

First Ten Sentences of Becoming Anabaptist #

Here’s the first 10 sentences of Becoming Anabaptist: The Origin and Significance of Sixteenth-Century Anabaptism

Here is a book that is against just about everything we believe in.

I say that as a Methodist bishop who ought to know what we believe in.

Methodists are those Christians who believe in trying to follow Jesus and attempting to be the church without letting any of that get in the way of our being successful.

In other words, we Methodists are just about everything that every Anabaptist lives in fear of becoming.

Denny Weaver knows, about as well as anybody, what Anabaptists believe in.

In this masterful treatment of his beloved Anabaptist vision, he writes in measured, scholarly, orderly fashion. But I warn you: Do not be deceived by his Mennonite reserve.

This book is a clinch-fisted protest against what the rest of us have made of the church, a defiant act of resistance against the predominant American way of being Christian, a song of love (disconcerting thought—Mennonites making love) to a Jesus that the rest of us are reluctant to follow and a people who, in every generation, Jesus has loved into being out of nothing.

To subvert the present ecclesiastical order, Weaver on nearly every page of this book lures us into a respectful discussion of how Anabaptists got here and what they believe. Typical of the Mennonites I have known, he politely reassures us that he is a pacifist Christian who bears us no harm, then hands us a ticking bomb.

Emphasis mine

What’s you’re gut reaction right now? These ten sentances are strongly worded. Unexpectedly so.

Here’s a bit later in the same foreward:

One of the few things that all Catholics, Lutherans, and Calvinists could agree on in church history was that Anabaptists were a threat and ought to be killed.

Thousands died for their conviction that the church is called to more pressing business than to be socially significant, and thousands still die.

We’re all state churches now who don’t appreciate anybody walking around loose who is under the impression that there is a king other than Caesar.

Anabaptists continue to have the distinction of being among the few American Christians who can look at the United States of America and the body of Christ and tell the difference.

We Americans thought that we were open-minded, basically peaceful, well-meaning people until we met the Mennonites.

They have always managed to bring out the worst in us and to demonstrate the limits of our bogus “religious freedom.”

They have always served as a rebuke to the Niebuhrian claim that Jesus is a sweet-spirited idealist who is utterly irrelevant to responsible ethics.

Thousands died? Catholics, Lutherans, and Calvinists banded together to murder Anabaptists?

How can this be? How have I never heard of this?

Scroll down to Persecutions and migrations

Roman Catholics and Protestants alike persecuted the Anabaptists, resorting to torture and execution in attempts to curb the growth of the movement. The Protestants under Zwingli were the first to persecute the Anabaptists, with Felix Manz becoming the first martyr in 1527

The persecution of Anabaptists was condoned by ancient laws of Theodosius I and Justinian I that were passed against the Donatists, which decreed the death penalty for any who practised rebaptism. Martyrs Mirror, by Thieleman J. van Braght, describes the persecution and execution of thousands of Anabaptists in various parts of Europe between 1525 and 1660.

Other quotes #

I’ve got a few more interesting quotes from the book, this time as written by Weaver:

On page 229, Weaver addresses a modern response to the early history of the Anabaptists

Why was there was so much conflict anyway, like burning people at the stake and state-and-church-enforced drownings

He thinks that some of the modern scholarship completely misses the fundamental differences between the Anabaptists and state/church environment in which they lived.

He says it’s overwhelmingly likely that we modern folk who dismiss this conflict as “arcane disagreements about baptism” do not understand the root of the issue:

If Anabaptists, Catholics, and Protestants shared as much in common as [other modern scholar’s] approach implies, it would then follow that neither side understood the issues at stake (pun intended!).

[snyder proposed that] those who were killing Anabaptists did not realize how much like themselves the Anabaptists were, and Anabaptists were giving up their lives for a faith that was quite close to that of their persecutors.

The implications that neither side understood the situation seems contradicted by the arguments of [someone else], who said that the Peasants’ Reformation called for a restructuring of society that posed a clear challenge to the authorities, and that the authorities perceived that challenge.

It was this challenge to the authorities that provoked the violent response to the peasants that is called the Peasants’ War.

Anabaptists also posed a challenge to existing structures of church and society, even if a quite different challenge than that of the peasants.

Even when Anabaptists professed to be pacifists, their rejection of the state church and their rejection of the jurisdiction of political authorities in church matters were perceived as threats to the social order.

For the most part, Anabaptists were not martyred for a faith with great resemblances to Catholicism and Protestantism, but because Anabaptism posed an implied challenge to the existing structures.

Other Quotes #

Here are a few sentances from the appendix, answering the question “why do you refuse to talk about similarities between Anabaptists and other denominations”?

Starting with points of agreement intrinsically favors the side or the group that represents the dominant perspective.

The points of difference are the elements that distinguish the small or the minority viewpoint from the dominant group, and these are precisely the points that end up outside the core, relegated to the periphery and outside of the main discussion that focuses on agreements.

A dialogue that took both sides equally seriously would begin with points of disagreement, since it is these points that distinguish the minority position. Beginning with these disagreements would bring the particular identifying characteristics of the minority position to the heart of the discussion.

Another paragraph from the same appendix:

What distinguishes Anabaptists from other Christian perspectives is then not a deviance from Christendom’s norm, but the manner in which it appeals to Jesus’ story.

The credibility of Anabaptism as a movement thus depends on references to the story of Jesus rather than its agreement with the traditions of Christendom, even though Anabaptism emerged in conversation with these traditions of Christendom.

The question is where authority ultimately lies—in Jesus’ story or in later tradition.

It bears repeating at this juncture that distinguishing Anabaptism in this way is not an assertion or call for withdrawal. It instead is designating the basis on which Anabaptism engages in and interacts with the traditions of Christendom and with the social order.

In this light, Anabaptism is not a deviance from but a corrective for the traditions of Christendom, whose identification of the church with the social order is linked to not accepting Jesus as authoritative, particularly on the issue of the sword.

Hence, we return to the original thesis, that defining Anabaptism theologically in terms of core theology shared with Christendom traditions blends Anabaptism into Christendom rather than posing a prophetic witness to those traditions and to the social order.

I’d love your thoughts.

Update: 2020-06-28 #

two weeks after sharing around what you’ve so far, I’ve done more digging, have some more updates

So, I’ve gone down a bit of a rabbit hole.

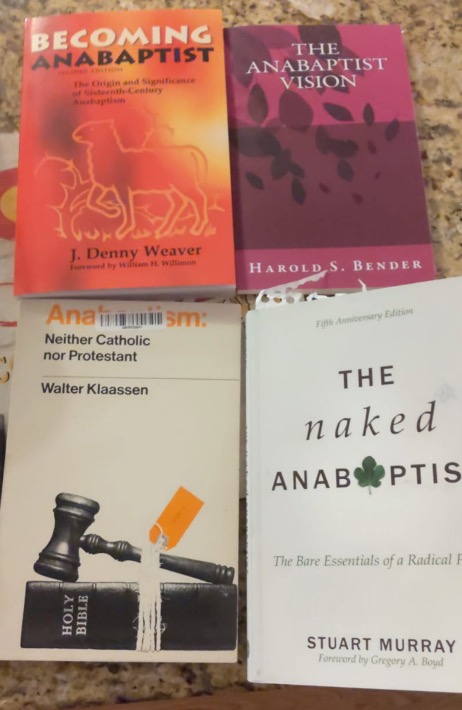

Here’s a smattering of the literature I’ve begun, though I have not finished:

Since posting the above, I’ve re-read Becoming Anabaptist, and read (for the first time) The Naked Anabaptist, in addition to some other unrelated books.

A thread is rapidly coalescing in my mind, and I need your help. So, lets continue this conversation via email, because so far, this is just me writing words to you. I want you to be able to respond.

Now that you’ve read this far, if you’re curious to keep digging (the story gets even better and more important):

If you don’t see the subscribe form above, click here.

I want your feedback and challenges on what I write.