Anki and Memorization with Spaced Repetition Software

Article Table of Contents

- Anki Spaced Repetition Software - Spaced Repetition Software

- Installing Anki

- Getting started: Your first card

- Building programming-related flashcards! - Resources on Memorization

This is not meant to be read in isolation. Memorization is almost useless without doing work ahead of time to grasp the material. For the full context, start with Learning how to Learn

I’ve not been able to find any comprehensive guides to using Anki to learn programming, so this article is a deep-dive on just that topic, from installation and configuration to building good programming-related flashcards.

We’ll cover a few pieces:

- What is Anki, and Spaced Repetition Software?

- Why would you use it?

- Getting started: Your first card

- Configure Anki on your phone

- Markdown and Anki

- Install Markdown Package

- Using the Markdown package

- Building a good first programming-related flashcard

Anki Spaced Repetition Software #

Anki has been one of my favorite tools I’ve encountered in the last few years. I started using it initially for learning Spanish vocabulary, but as I started learning programming, it really started to shine.

Anki is a flashcard application that attacks the issue of “memory decay” to retain and strengthen recall of anything you want.

Spaced Repetition Software #

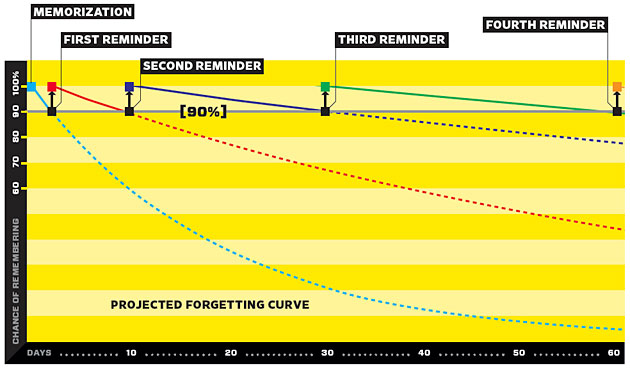

If you learn something today, you might remember it tomorrow, but will probably forget it in three or four days. However, if you review it before you forget it, it’ll “stick” in your head for a bit longer than it did the first time you learned it. This “forgetting curve” can be bent exponentially in your favor.

Here’s how remembering (and forgetting) over time tends to play out:

The goal here is to create relevant, well-formatted bits of knowledge, and then get them in Anki and review it the minimum amount of times to ensure that we’ll remember it for a very, very long time. (I.E. so long I can never forget it, so several years, at least)

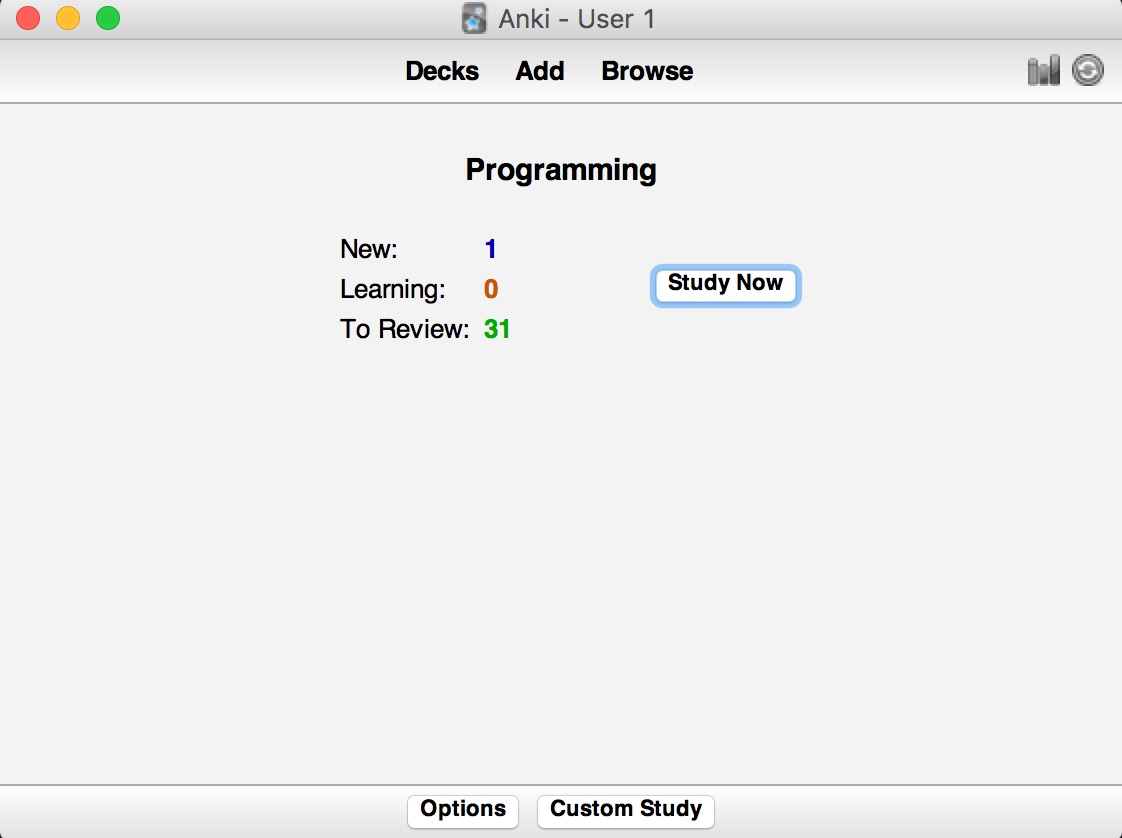

On first blush, Anki has an unassuming user interface.

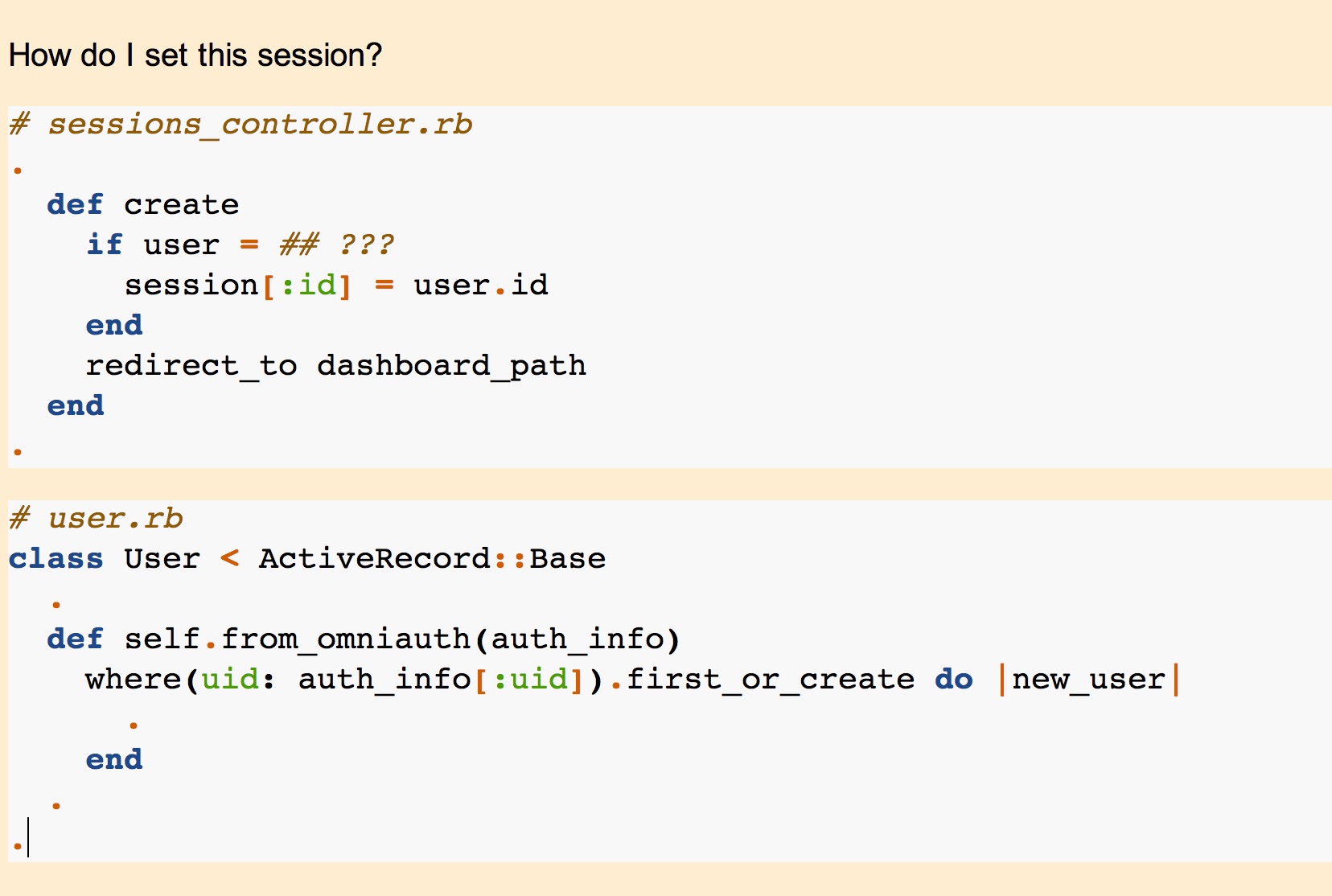

Continuing the example from learning how to learn, here’s the ‘front’ of one of my flashcards:

This card looks complicated, but it’s actually easy. You’ll notice that I basically gave myself the answer in the question setup. I’m simply training myself to recognize how I set up the User class, and that it has a class method from_omniauth, and building a mental model of how I use request.env["omniauth.auth"].

the answer is:

if user = User.from_omniauth(request.env["omniauth.auth"])

And I prefer easy flashcards (more work to make, less difficult to recall) than difficult flashcards.

For Anki’s basics, go check out this excellent guide: Spaced Repetition.

I put all sorts of information in Anki. At the moment I have about 850 1200+ programming-related cards, which covers many topics related to software development.

I’ve got cards related to:

- Ruby and Rails

- Linux terminal commands and their options, like

grepandxargs - Git/Github

- JavaScript

- HTML/CSS

- SQL

- Regular Expressions

- iTerm & Atom keyboard shortcuts

I am confident that I have not found the ideal workflow around creating and memorizing Anki cards. I’m still trying to improve this process, but the benefit of using Anki far outweighs for me any cost of having less-than-perfect cards.

My Anki workflow has two steps:

- Make the Anki cards on my laptop

- Review the Anki cards on my phone

I can review my Anki cards anywhere. In line at the grocery store, in the bathroom (yes), on a train, while I’m waiting for my food to microwave, etc.

I normally hate to be the person staring at his phone all day, but since I’m usually on Anki, I now embrace it.

According to PhoneUsage I spend between 30 and 45 minutes on Anki review per day, and it’s all in little snippets of time grabbed here and there. (a bit about how I manage my phone usage every day here)

Two primary benefits #

Cool, Josh, all this sounds nice, but it is a lot of work, especially to spend 30 minutes or an hour every day building and reviewing note cards. I’m busy, and if I’m learning programming, I’ll be even more busy than I am now.

Why is Anki better than just studying a topic more?

1. The process of recalling answers from memory solidifies subtle-but-important details #

There are lots of small-but-meaningful details we encounter when trying to make computers do our bidding.

The presence of a comma in a list of arguments, or if a method is a class or instance method, or if that git reset command uses --HARD as an argument - these all can introduce tiny bits of friction in our goals. I see a lot of what I am memorizing as not necessarily just learning new things, but making sure that the things I have learned, I know very well.

For example, if you’re not sure how the params of a post request are formatted, once you’ve built and memorized a few cards related to this formatting, you can better access elements in that hash because you already know the basic structure to expect.

Alternatively, are you 100% sure of the format for building a .reduce iterator? What’s the difference between [].reduce() do |result, item| and [].reduce({}) do |result, item|? With a few note cards on building/using the reduce method, you’ll spot the difference immediately, and know how to reason about it.

These are subtle but important details. Remember - computers are not that smart, they’re just extremely literal. Details make or break everything you build.

2. This memorization functions as a progress-capture device for new things you learn #

How often do you use a new method, or try to implement a basic feature, and you are positive you’ve encountered the topic before, but cannot remember what you actually did?

You’re off to the docs, or looking at previous projects, until you refresh your memory.

This is fine, and even with Anki you’ll be regularly referencing documentation and prior code, but you’ll do it much less, because so much of what you’ve seen before you’ve memorized. It’s just sitting in your brain, ready to be used again.

Sometimes, even though I’ve memorized cards, I cannot quite reproduce the whole chunk of knowledge from scratch, so I just open up the Anki and find the card that relates to the thing I’m trying to do. It’s a bit like keeping detailed notes and always knowing exactly where to find the relevant information for what you’re looking for.

Or, that one time I had to rename a branch in Git - what was the exact syntax for pushing the deleted branch? Did I actually rename the branch, or did I use the git branch -m command to create a new branch? (hint - the next step is git push origin :old_branch_name, then push the new one with git push origin --set-upstream origin new_branch. I just opened up Anki to check the steps. Super simple.)

Installing Anki #

Download the desktop app at https://apps.ankiweb.net.

Download it, install it, and open it up.

Getting started: Your first card #

Make a new deck. Call it “programming” or “test deck” or whatever. Now click the “new card” button.

Lets create a sample card. Don’t worry, you’re doing to delete this card in a minute, so it doesn’t matter if it’s “good” or whatever.

In the box labeled “front”, put “what is my name”. On the “back” put your actual name. Or perhaps a more relevant question, like:

Front:

Who writes the most long-winded and rambling blog posts in the world, and embarrassingly refers to himself in the third person every now and again?

Back:

Josh Thompson

Make two or three cards. It will be easiest to see how Anki works with more than one card in the deck.

Now, lets review your cards. Hit the “Study now” button, and think hard about the answer to the first card.

For purposes of explanation, lets say you cannot remember either your name or my name. Admit defeat, and click the “show answer” button.

Since you couldn’t remember, click the left-most button on the bottom, that says <10m, Again.

This button is how you signal to Anki that you didn’t know the answer, and the card will immediately be re-queued for you to study within the next ten minutes.

Once you click the button, the next card will show up. Lets say you do know the answer to this question. Click “show answer”, and then click the button labeled “good”.

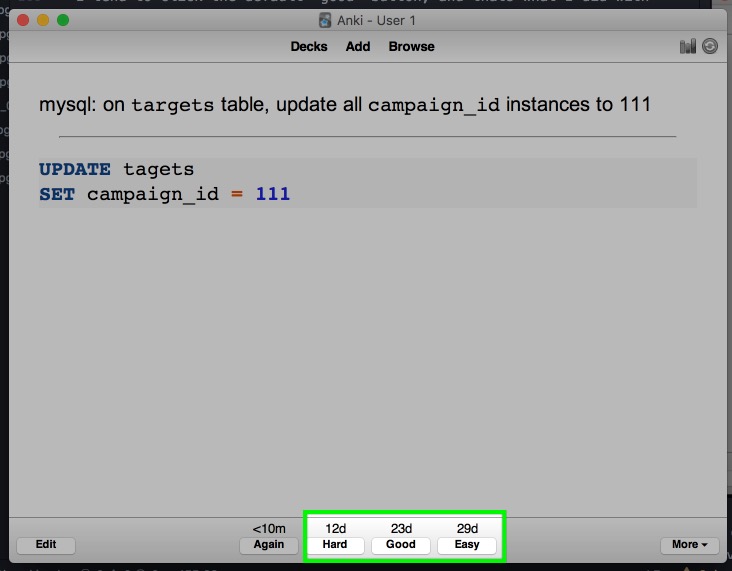

You’ve got three options when you’ve recalled the right answer. They are labeled “hard”, “good”, and “easy”. Depending on which one you click, the time that will elapse between now and when you see the card again will change.

If the answer was hard for you, you want to see the card again soon. If it was easy, you’d like it to be a longer period of time before seeing it again.

Depending on how many times you’ve reviewed the card, the time intervals associated with the card will change.

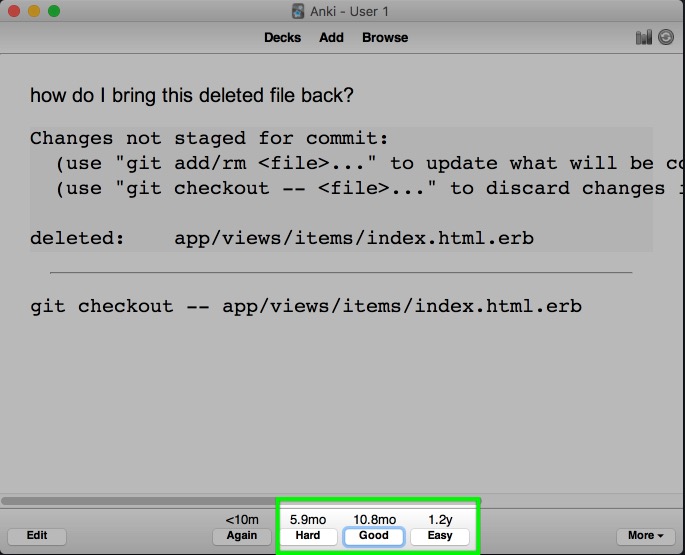

Here’s the intervals I am seeing on some of the cards I’ve reviewed today:

If I click the “Hard” button, I’ll see it again in 12 days. If I click easy, I’ll see it in almost 29 days.

I tend to click the default “good” button, and thats what I did with this one.

Here’s another, older card, where I can decide if I want to see it again in six months, 11 months, or 14 months:

You’ll get a feel for how this works, and what are the best answers for you, as you go.

The next step is to hook up Anki and your phone

Configure Anki on your phone #

Since you’ll be building cards on your computer, but most likely reviewing them on your phone, we’ll go ahead and get Anki working on your phone.

Download the phone app:

The iPhone app costs $25. The Android app is free, the iPhone app is not. $25 seems like a lot. The author explains this price here. According to my phone’s stats, I’ve spent 96 hours of active flashcard review time with Anki at the time of this writing, which boils down to $0.25/hr. I consider this to be an extremely good use of my time and money. Look for the value, not the cost.

Create/sign in to your AnkiWeb account #

1. Sign up for a new AnkiWeb account #

2. Sign into your AnkiWeb account on the desktop Anki application #

get screenshot of what it looks like not signed in to an account

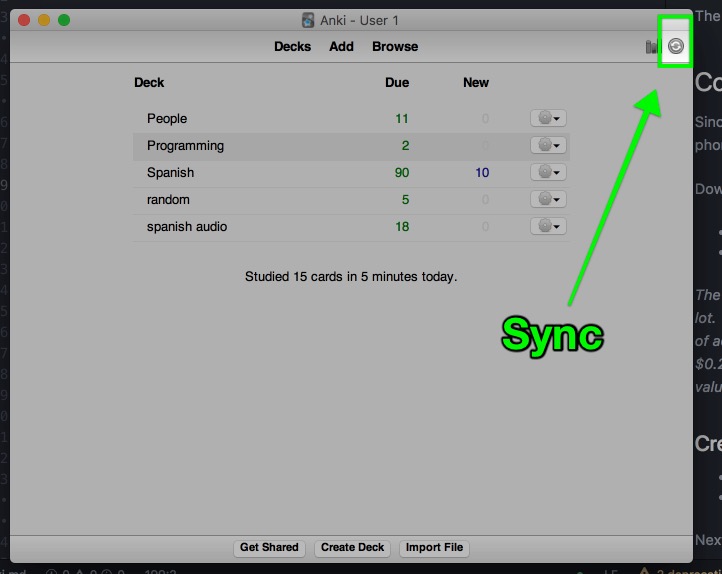

In the desktop application, hit the “sync” button:

3. Sign in on the phone application. #

For Android, you’ll the following, in this order:

- Tap the hamburger menu

- Tap “Settings”

- Tap “AnkiDroid general settings”

- Tap “Sign In to account”

<sign in, need pictures from different account>

Now hit the “Sync” button on your phone:

phone screenshot here

And you should see the info from your desktop showing up on your phone!

Take a deep breath. This is a big accomplishment, and you’re most of the way done with getting configured on Anki!

Markdown and Anki #

Since we’re doing programming related flash cards, and one of the first rules of formulating knowledge is “specificity”, we want code snippets in Anki to look like code snippets on our computer.

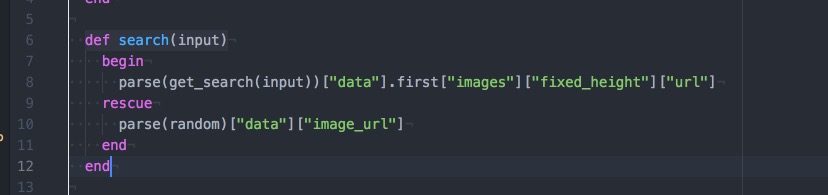

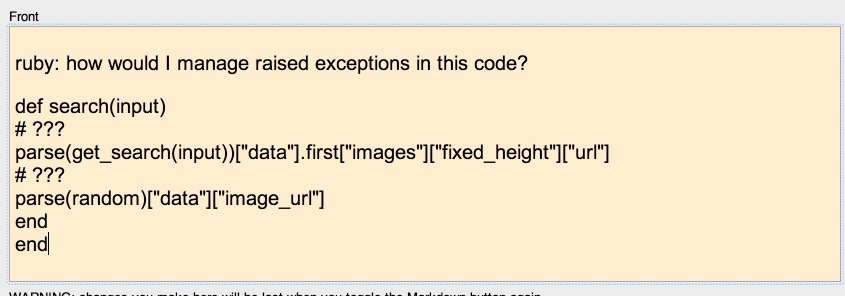

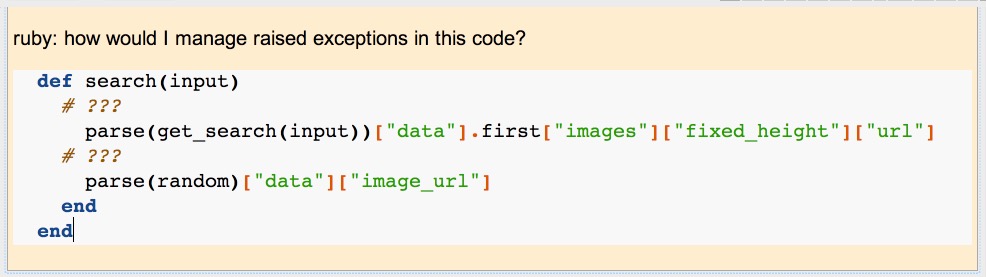

Lets say you want to make an Anki flashcard related to the placement of this begin and rescue in this chunk of code:

Which of these cards do you think would be more effective for learning?

Option one:

Option two:

The second option is much, much more readable and understandable.

To format your code like this, you’ll need to install (and use) a Markdown package.

Install Markdown Package #

We will be using the Auto Markdown package.

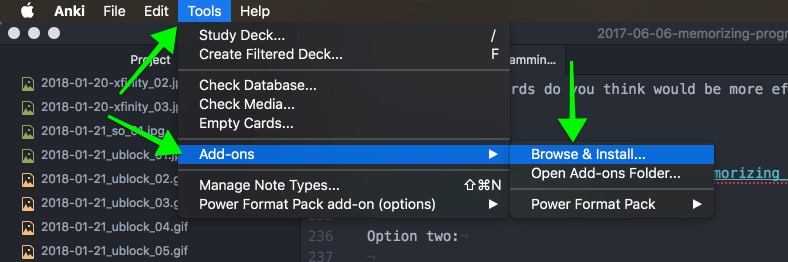

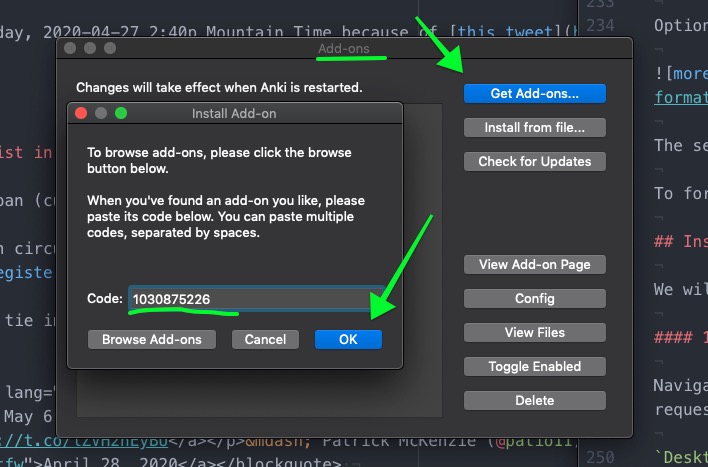

1. Add the Markdown package to Anki #

Navigate through the following menu, and entering the number 1030875226 when it’s requested. (The number is the end of the URL of the package we want.)

Desktop > Tools > Add-ons > browse and install

When you click the Browse & Install button, just enter 1030875226

2. Restart Anki, per the instructions #

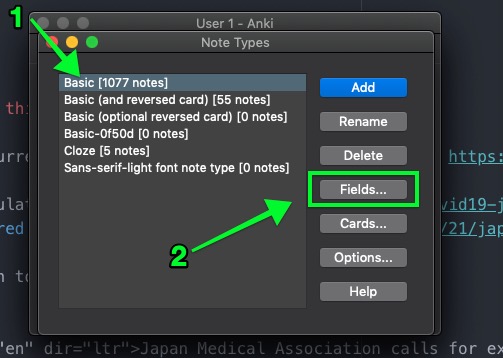

3. Enable the new Markdown package in Basic card types #

Check the “Enable Markdown” button. (It’s very buried):

Anki > Tools > Manage Note Types > Basic and click Fields

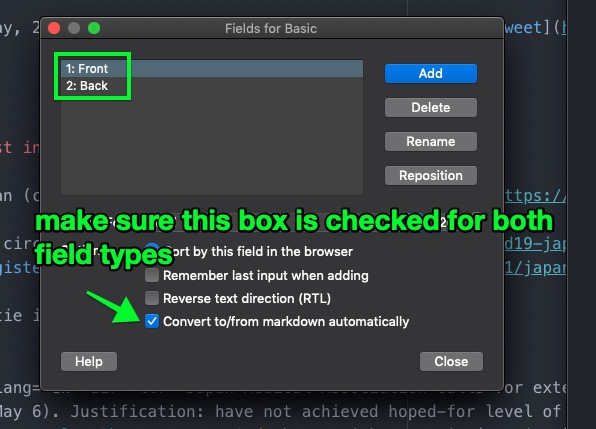

Next, for both the front and the back of the card, check the Convert to/from markdown automatically box:

4. Restart Anki again #

Using the Markdown package #

Markdown is great. I use it constantly. In fact, this entire post is composed in Markdown - all of my text formatting, code blocks, links, and images are written in Markdown.

If you don’t know Markdown, you can ease into using Anki by learning to use Markdown.

Let’s start with something basic - using fixed-width color offset to draw attention to technical language.

Backticks to make text formatted and fixed-width #

“Visual hierarchy” is a huge way to help the human eye differentiate the important from the unimportant, or between things of different types.

Here’s two was to write the same question. This is a question I asked someone on my team recently:

what value do you use for SIDEKIQ_PORT in config/application.yml?

Compare that with:

what value do you use for

SIDEKIQ_PORTinconfig/application.yml?

The one with the text formatting is easier to understand. Lets extend this principle to building programming-related flashcards.

Imagine an Anki card that says:

what does array.sort do?

You can draw a little more attention to the specifics of the question (it’s about an Array, and it’s an instance method!) by using:

What does Array#sort do?

But that doesn’t catch the eye nearly as well as:

What does

Array#sortdo?

So, to off-set text like that, you just “wrap” it in backticks, the key to the left of the 1 on your keyboard.

This is what text that’s been

wrapped in backtickslooks like

Important note: This markdown package has a super annoying bug in it. I couldn’t figure out the fix at the code level for everyone, but if you have your mac in “dark mode”, the markdown formatting will look HORRIBLE! here’s an open github issue and the fix

So, make a card like this in Anki:

What makes text monospaced? backticks!

Make a few more cards. For example, figure out how to make a large block of pre-formatted text, or give a block of code language-specific syntax highlighting.

(You can use ruby, javascript, html, css, pretty much any language name and get appropriate syntax highlighting)

Building programming-related flashcards! #

Wahoo! You’ve almost made it! The end goal is in sight!

I’d recommend keeping two points in mind before proceeding:

1. Go slow #

I have a cap for ten new cards a day, even if I make twenty flashcards. Experiment with what works for you, but swamping yourself with cards makes it less likely that you’ll stick with the tool.

Here’s how to set the maximum number of new cards a day. I would set it to about seven:

2. Build multiple cards around each discrete piece of knowledge you want to acquire. #

If you want to remind yourself of how to use .map in Anki, make three or five different flashcards, testing it from different directions.

For example, card 1 might be:

Front:

What method can I call on an array to iterate through each item,

and it returns the mutated array?

Back:

Array.map

Card 2:

front:

what do I call to add 1 to each number?

[1, 2, 3].? do |num|

num + 1

end

back:

[1, 2, 3].map do |num|

num + 1

end

=> [2, 3, 4]

Card 3:

Front:

letters = ['lkj', 'kwidk', 'wwid888']

What's a one-liner to make all above letters capitalized, so that:

big_letters = ["LKJ", "KWIDK", "WWID888"]

Back:

big_letters = letters.map { |w| w.upcase }

=> ["LKJ", "KWIDK", "WWID888"]

Next, read a bunch of these articles below, and go forth and prosper!

Oh, and if you’re like me and love using screenshots in Anki, go for it! I use Annotate.app, but any tool will work. Make your screenshot, and drag it into Anki, and it’ll be ready to use.

Resources on Memorization #

- Effective learning: Twenty rules of formulating knowledge

- Spaced repetition: Never forget vocabulary ever again (in the context of language learning, but perfectly applicable to programming)

- Memorizing a programming language using spaced repetition software

- JANKI METHOD: Using spaced repetition systems to learn and retain technical knowledge.

- Markdown code formatting in Anki

- Spaced Repetition

- Anki tips

- Wired Magazine: Want to Remember Everything You’ll Ever Learn? Surrender to This Algorithm