On Learning

Article Table of Contents

- Overview of Process

- Steps to try to learn something

- 1. Define the boundaries of the topic

- 2. Find a way to play with the component pieces.

- 3. Write down, on real dead trees, the component pieces of the process.

- 4. Write down again, at a higher level, the involved pieces.

- 5. Get a few “reps” of implementation.

- 6. Capture some of the high and low level details in Anki.

- Conclusion

As a student at Turing, I’ve recently been thinking about learning how to learn, specifically in the context of software development.

I am a bit hyperactive when it comes to trying to learn new things. Over the years, I’ve done plenty of ineffective learning, and at least a little bit of effective learning. The good news is that even as I’ve not learned most of the topics I’ve originally set out to learn, I have learned a bit about learning. (Does this make it “metalearning”?)

I’m defining “learning” or “learning a topic” as to be able to rearrange or reorganize or reuse the idea or pieces of the idea in new ways to resolve unstructured problems I face.

This “rearranging/reorganizing” and “unstructured problems” explicitly excludes the kind of learning most of us have done when we were young, where we just tried to have the right answer for fill-in-the-blank questions like “In _____(year) Christopher Columbus sailed the ocean blue”.

Overview of Process #

All things worth doing should fit into some sort of process. If there’s no process, I’m just shooting in the dark, hoping to hit something. That said, the right process is almost always not the first thing I try, and I’m usually skeptical of “expert advice”, for many reasons. So, I like to try to pick a reasonable starting point, and experiment with process from there.

Additionally, even a loosely-defined process reduces friction to attempting the thing. If, every time I came across a difficult concept in programming, I had to decide how to approach learning it, I’d waste time and energy deciding how to learn the thing.

But, since I have a process, as imperfect as it is, I can just say “ah, a hard thing. Time to attack it with my six-step process to learning difficult things”.

I’ve been thinking about friction, and learning, and the relationship between the two, for quite some time. For example:

Here’s my current iteration of “how to learn difficult things”

Steps to try to learn something #

1. Define the boundaries of the topic #

If you want to learn Software development, that has no boundaries.

If you want to learn Session management in conjunction with OmniAuth, you can actually figure out what you need to learn. It’s better-bounded.

The more specific I can be about what I am trying to learn, the better I can approach the process. I also always try to find the smallest viable chunk of the topic, and start there. So even session management with OmniAuth is contingent upon having a notion of how session management works, so I would start with just understanding sessions, and THEN move to OAuth, and THEN move to OmniAuth, and THEN roll everything together.

2. Find a way to play with the component pieces. #

One of my end goals of learning is to build an accurate mental map of the process. I need to be able to visualize how the pieces fit together, and what each piece is composed of. In a REPL session, I would spend a few minutes “playing” with the object that OmniAuth returns in the user is authenticated.

For example, the core piece of OmniAuth comes back to the requesting service inside of request.env, which is a HUGE hash. So, after looking at it, I can figure out that the OmniAuth hash is at request.env["omniauth.auth"]. That hash contains all the user details, a uid, and more.

(With the Omniauth example above, the “object” that comes back from a successfully logged in user can be accessed in the request. So, I’d look at the request object, the request.env object, the request.env["omniauth.auth"], object, request.env["omniauth.auth"].keys, and examine each of the sub-pieces.)

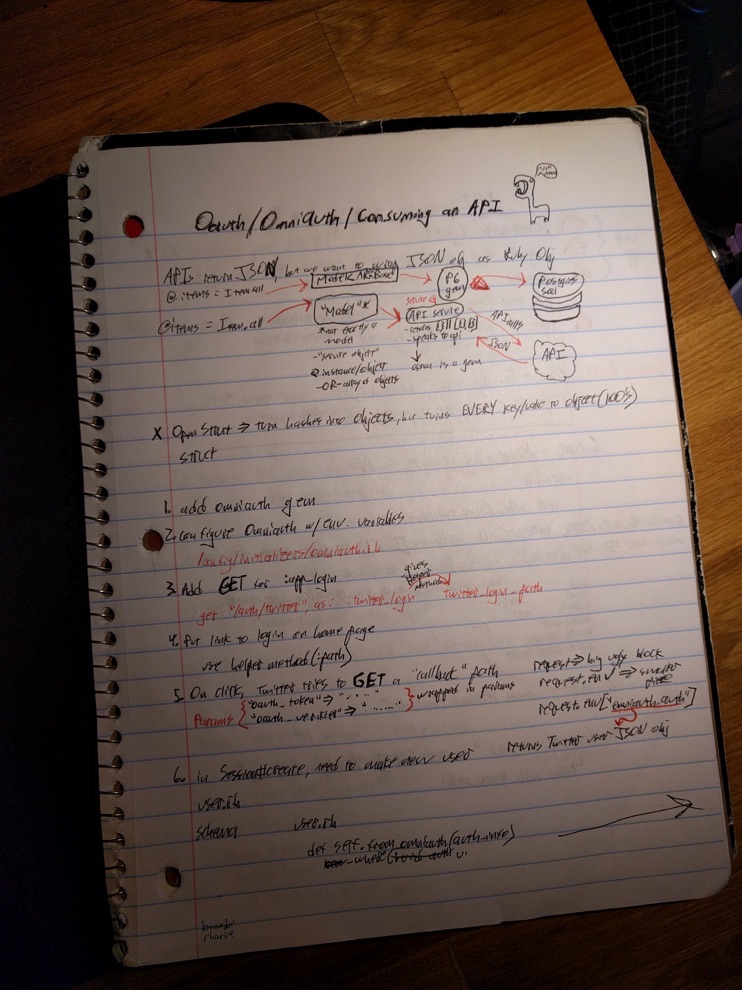

3. Write down, on real dead trees, the component pieces of the process. #

At a low level, this is actual code blocks, and once I get the individual pieces (for example, using a from_omniauth(auth_params) method with first_or_create_by to query my users database) I’ll then write out the associated piece of code next to it. So, if I’m moving between a user model and sessions controller, I’ll write both code blocks side by side. I can easily add in the related routes and views, and anything else that fits into the process along side.

Something that is important to me is having pens of two colors at hand, and using one color for all my text, and the other one to draw arrows between things.

The arrows are the core piece of finding and identifying relationships inside my code, and accross files, so I think it’s pretty important.

The process of writing code out, by hand, helps me identify the many wrong assumptions I make about the code as I am reading it. It’s critical to me, but most people don’t take these sorts of paper notes, so I might be an outlier. Everyone in the class is learning the same stuff, and learning it well.

4. Write down again, at a higher level, the involved pieces. #

At this point, I might just be writing down the involved object types, and their associated methods. I.E. I am for a “cheat cheet” of notes that I can look at and refresh my entire knowledge of the topic. This means instead of individual code blocks, I might list the flow or progression of the code execution through the application, noting what are the involved files and pieces.

For user authentication, it will touch:

- routes

- Sessions controller

- User model

- user database

- Possibly a service

- a view or twoÂ

- etc.

I capture each of these pieces on paper. This way I’ve got a detailed and higher-level mental model of what is happening.

5. Get a few “reps” of implementation. #

If I was following a tutorial, I’ll delete the work I just did and implement again, without referring to anything but my paper notes. (This is a sanity check to make sure I captured the right information on paper. Often I’ve not caught enough, so I modify my notes.)

6. Capture some of the high and low level details in Anki. #

This section was getting longer and longer, so I split it into it’s own post. Read on about memorization and spaced repetition software here –>

Conclusion #

After working through these steps, I can usually say I’ve attained my goal of learning the topic. If I have not learned the topic, I’ve probably bitten off more than I can chew, and should revisit my original learning goal.

I’ve certainly have not learned everything about the given topic, but I have a mental framework on which I can hang further learning, and I can take the low and high-level knowledge and either apply it in other similar projects, or recognize the patterns of others using it in their projects.

My goal is to get the minimum effective dose of learning so I can move on, but not lose what I’ve just spent a while working on.

The notes and implementation practice helps me learn the thing, and Anki keeps me from losing it, so it’s quick to bring to mind weeks and months later.

Full disclosure - this is a time consuming and difficult process. I don’t do it every day, though I wish I did. To buckle down on a topic like this necessarily requires NOT attending to other topics I could be studying. Life is full of trade-offs, but in general I’d rather learn one thing well than four things poorly.