How to Ask Questions of Experts To Gain More than Just Answers

Article Table of Contents

- Why do questions matter?

- Traits of a bad question

- Traits of a good question

- Examples

- Optimize for learning, not just the answer

- Better questions, better everything

- Checklist for asking questions

- Additional reading

Recently, I co-led a session at Turing with Regis Boudinot, a Turing grad who works at GitLab.

We discussed two things:

- asking good questions

- having a good workflow

After the session, I promised an overview of what we discussed. Here’s that overview for “Asking good questions”. Get info on “having a good workflow” here

Why do questions matter? #

Without getting too philosophical, the process of formulating questions and finding answers to them is a big part of what makes us human.

As developers, we’re asked to solve difficult problems. If we don’t happen to have all the knowledge we need for this problem readily accessible in our head, we turn to documentation and googling.

On many problems, this is sufficient. On the hard ones, this will not be sufficient.

We’ll need to ask for help.

Since the hardest problems are also the ones we’re most likely to need help with, if we can optimize how we get help, it’ll return outsized results at advancing our skills and helping us be useful contributors to a development team.

As a counterpoint, imagine you had terrible question-asking skills. In what aspects of your day-to-day would this have the largest impact?

- The things you already know how to do

- The things you don’t already know how to do

Exactly! Questions matter.

Traits of a bad question #

Lets rollplay a bit. If you’re a student at Turing, and you have a friend considering attending Turing, and they sent you an email with the following sentence, how would you feel?

Hey there, Turing sounds cool. I’d like more information. Can you send me a link to their website, let me know the tuition, and let me know what the likelihood is that I’ll graduate with a well-paid job? Thanks!

Yikes.

It looks like this person didn’t do one iota of research on their own. Finding the website of something is Googling 101, and they’re also asking you a very complex question that you couldn’t hope to answer without more information from them. (The likelihood that they’ll graduate with a well-paid job. How do you define well-paid? How hard will they work? Do they mean a job on the day the graduate or are they willing to include a job they might find in the next two weeks?)

It’s also a bit of a selfish question. We’re all selfish, but this is showing an interest only in the results, and not the process.

Lets look at some other bad questions. (Some detail removed to protect the guilty, but all are pulled from Slack channels over the last few days.)

I can’t get [tool everyone uses] to work and I don’t know what I’m doing wrong

This was a real DM sent to a contemporary. No additional context, nothing. Just that one message in Slack.

Does anyone know anything about [topic]?

This was a message posted in a public channel where anyone can ask questions and get help from others in the community.

Does anyone have a few minutes to pair with me on [current project]?

All of these questions were these one-liners, dropped into a public channel, where many of those that might be reading are domain experts and it is very reasonable to assume the right person with the right knowledge would see this message.

All of these questions are bad because they assume the other person (the expert) is willing to ask further clarifying questions, or get wrapped into a conversation or pairing without any additional context.

Traits of a good question #

Since we’re solving a hard problem, it’s reasonable to assume that the person helping us will also agree that it is a tricky problem. Even if it’s not “tricky”, they will need to “load up” the problem space into their head to understand what’s going on.

For example - if a method isn’t doing the thing you expect it to do, someone probably needs to see the following before they can even hope to offer something useful.

- the entire class

- what object is being passed into the method

- what object is expected

- what tests you’ve written

- more

This means that you probably will not be so lucky as to get a silver-bullet solution.

At a high level, when asking for help, aim to provide the “boundaries” of the problem space at the outset.

Something like

I’m having problems running migrations on my app. It WAS working a few minutes ago, now it’s not. I’ve tried dropping/resetting my tables/db,

bundleworks just fine, my PG server is running, and I can access my ActiveRecord objects viarails console. It’s only when I try to run RSpec that I get warnings about unfinished migrations, but their recommended fix doesn’t work.

This could still contain much more information, but it’s enough that someone can figure out what you’re working on, and has some context when they try to help.

Contrast that question with this alternative:

Can someone help me with my migrations? They’re not working and I don’t know why.

Lets talk about question workflow. If I have a problem that I cannot resolve, I open up a markdown file and start throwing notes into it.

I am to be able to answer the following questions:

- What am I trying to do?

- What have I done?

- What evidence am I getting that something isn’t working? An error message? Something not calculating correctly or returning the expected results?

- What different approaches have I tried?

- What is all of the involved code? (Yes, I’ll copy and paste blocks of code into the document.)

- If the problem is in my code, what tests do I have that are related?

- What are the resources I’ve looked at in pursuit of this problem? (This is usually just a link of stack overflow posts, blog posts, etc.)

Once I’ve pulled all that into a single document, I’ll add a quick summary at the top, push all the links to the bottom, and organize the code snippets a bit.

At this point, I’ll throw it all into a gist and pass it along to someone who is willing and able to help.

I treat the entire document almost as a letter.

Examples #

MiniTest setup questions #

In Mod 1, I was having problems with MiniTest setup methods. It was slowing our tests down. I really wanted to fix it, so I sent this gist to a mentor. His answer was very helpful, very focused, and exactly what I needed.

MySql usage problems #

In mod 2, I was trying to practice my ActiveRecord queries, which “compile down” to just SQL queries, so I was studying SQL. I was workin through a book that included tons of sample data to play with, but couldn’t load it up.

I wrote this gist after Ed G kindly offered to help. I sent him the gist so he could understand the problem space, and it was helpful.

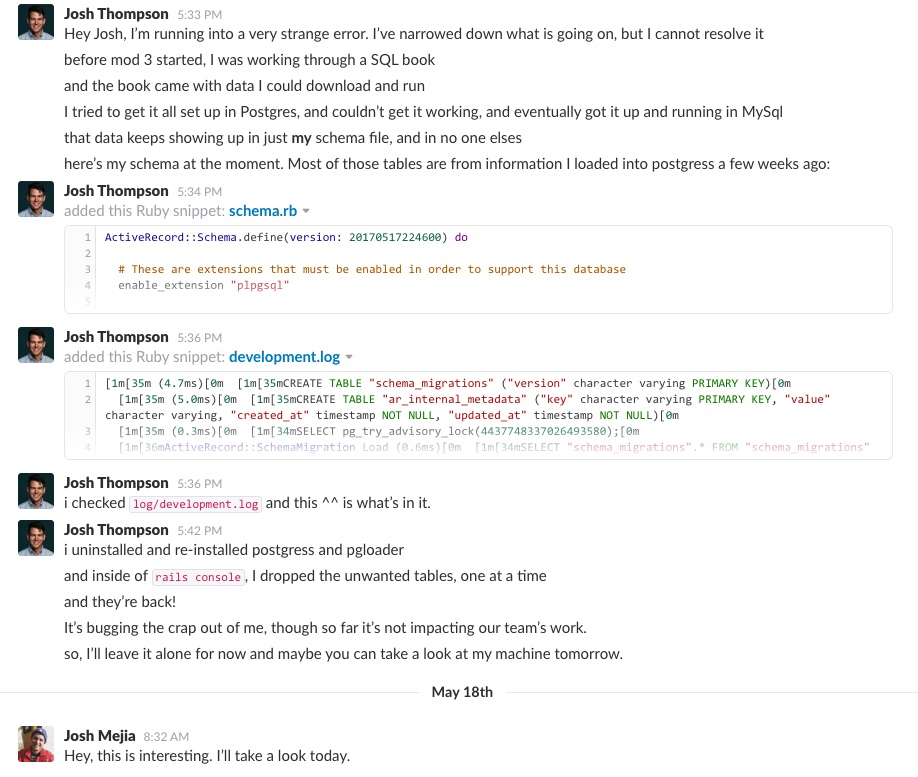

Rails Schema problems (related to the above MySql data importing!) #

More recently, I was having problems with the schema in a group rails app. My schema was getting loaded up with tons of tables that were nowhere to be found in my migrations! It was baffling!

I sent this to our instructor:

That gave us a starting point, and forced me to be very thoughtful in all of the solutions I tried.

Optimize for learning, not just the answer #

We often feel like we just need the right answer, and we’ll be on our way, when the truth is, the most important thing for us is better understanding. In the last question, with extra tables showing up in my schema, it turns out I had two instances of Postgres running on my machine. One showed up only as a running process, the other in the postgres app. One had a bunch of table in it, and I couldn’t see it.

So, after kicking around some troubleshooting, Josh figured that out, and I uninstalled both, then reinstalled just one.

My understanding of Postgres on my machine is much improved, and I now have a better idea how to troubleshoot similar problems in the future.

If Josh had just given me the answer, without the understanding behind it, I’d barely be improved.

You should seek to get the same sort of help from those around you. It’s tempting (especially when a student in Turing) to aim for the right answer. You might think you don’t have time to deepen your understanding when you have a project due in 12 hours, but really, you don’t have time to NOT deepen your understanding.

Better questions, better everything #

I am paraphrasing a recent conversation:

A mediocre developer who asks good questions and can communicate well can become a bigger contributor to a team than an experienced dev who doesn’t communicate well

So, here’s a checklist for the next time you need help. Write down the answers to these questions, and you’ll get understanding instead of just an answer, and whoever helps will be much more likely to enjoy the process.

Checklist for asking questions #

- What you are trying to do.

- What steps have you taken so far?

- What errors have you seen?

- What sources have you consulted in your search for these answers?

- What is the TL;DR?

- Have you included relevant code snippets or stack traces?

This puts the burden of asking questions on you, instead of the person you’re asking for help.

If you don’t provide this information, the first thing the other person will ask is

What are you trying to do? What steps have you taken so far? What errors have you seen? What have you done to try to fix this? Can I look at some code?

Good luck!

Additional reading #

- How to ask good questions by Julia Evans

- How to answer questions in a helpful way, also by Julia Evans