Some Lessons Learned While Preparing for Two Technical Talks

Article Table of Contents

- Things that went well

- Things that went poorly

- Lessons Learned

- It’s possible to plan for not knowing where you’re going

- The slides

- The results

A few weeks ago, I gave two talks about Ruby and Rails:

- An 8-minute lightning talk about using

.countvs.sizein ActiveRecord query methods - A 30-minute talk at the Boulder Ruby Group arguing that developers should embrace working with non-development business functions, and the constraints therein. I illustrated this via a story about finding slow SQL queries, and using

.countvs.sizein ActiveRecord query methods.

Things that went well #

- I enjoyed actually giving the talks

- I heard positive feedback after-the-fact

- I learned a lot from the process, and next time the prep will be much less anxiety-inducing

Things that went poorly #

- I felt quite anxious in the ten days or so leading up to the talks, thought it was because I was procrastinating.

- I felt stressed and shameful about not having the talks prepared.

- I did not finalize either talk until few minutes before leaving to give it, and was up late at night the night before each talk, doing the lions share of the preparation, therefore I was sleep deprived.

Lessons Learned #

I’ve got a few lessons learned from the process that will inform the next time I do a technical talk. I expect this will be iterative, and I expect I’ll continue to learn about this process for a while.

Motivation Matters, and intrinsic motivation is much more powerful than extrinsic motivation #

I initially volunteered to give the talks because many people I respect have indicated that it’s a healthy thing to do. I also believe that the opportunity for the most personal growth overlaps with areas of great discomfort. I really did not want to give a talk, so I knew that it would be good to do so.

So I said I’d give a talk, knowing that I had weeks to prepare. I volunteered to give a talk with only a loose idea of what I’d talk about.

I spent most of my time leading up to the talks worrying about what I was going to talk about, and what technical topic I knew well enough to dive into and explain to a bunch of quite experienced software developers at the Boulder Ruby Group. I thought:

I have nothing useful to say. They’ve forgotten more about Ruby than I will ever know.

I got unblocked from this problem late in the game. I found Preparing for a Tech Talk, Part 1: Motivation, and started thinking about this problem from the other end.

A few quotes from the article that hit home for me:

Internal vs. external motivation: #

Maybe giving talks is a part of your current job. Maybe you want to gain more recognition in the industry so you can land a better job or get a raise… We’ll call these motivations external. […] Maybe you find it rewarding to teach people. Maybe you enjoy learning, and giving a talk is a nice excuse to dig deeper. Maybe you want to start or change the conversation about a topic. Maybe you want to amplify or critique an idea.

Such internal motivations aren’t a proxy for another desire like professional recognition. These are the things that have intrinsic value to you.

I realized I’d started the process of giving the talk with external motivations, but I wouldn’t be able to make a talk that didn’t suck until I’d uncovered the right internal motivations.

Instead of thinking

What do I know well enough to talk about to seasoned professionals

I thought

What do I know, or what perspective do I have, that might be interesting and maybe even useful to a crowd of experienced software developers?

Turns out I’ve got stuff there, and a few stories that could prove to be instructive.

My Motivations #

I love to share knowledge and teach things.

This website is pretty strong evidence of that, and I spent a lot of time helping people learn things about software development, rock climbing, career navigation, and more. It’s a strong unifying thread throughout many domains of my life.

Sometimes it’s a “direct knowledge transfer”, where I simply have a piece of knowledge that they don’t, and I give them that piece of knowledge. This is rare, though. I’d say 90% of the time, I “teach” through a collection of ideas, like: process, my experiences, and stories of failure (and success).

- I might share a process around something. (Finding a bug, resolving a stack trace, feeling confident while lead climbing)

- I might share a story of failure that illustrates a concept. (I failed my last project coming out of Turing, and I got an F my last semester of college, and got a “provisional” diploma until I finished an online class to hit some credit requirement. The concept is

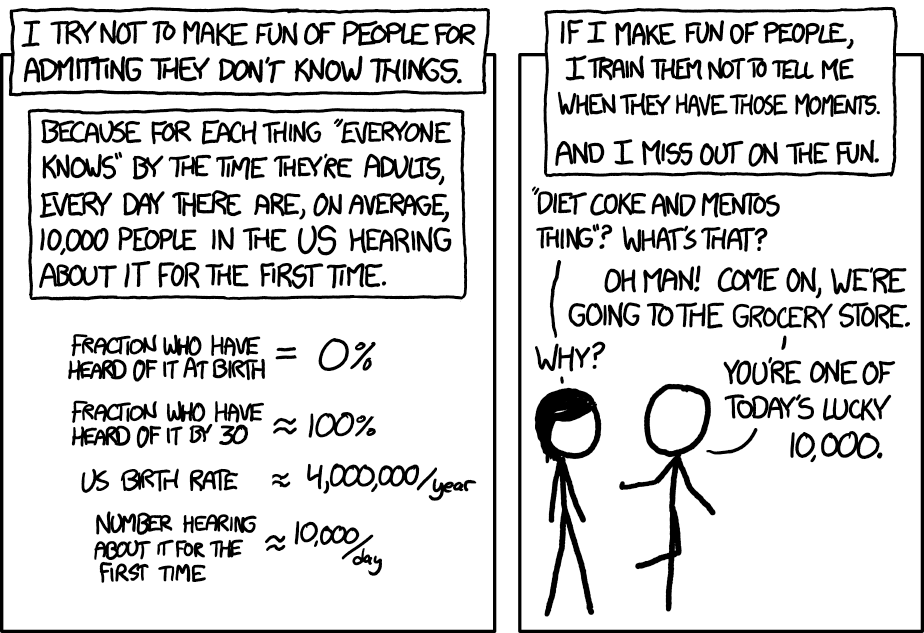

good_grades != good_education && bad_grades != bad_educated. There’s a loose relationship at best between grades and the vast majority of knowledge one might acquire.) - I know so little about so much, so even if I share just obvious things, it’s likely that others will be helped, via the Munroe’s “Today’s Ten Thousand Rule”:

mouseover text: Saying ‘what kind of an idiot doesn’t know about the Yellowstone supervolcano’ is so much more boring than telling someone about the Yellowstone supervolcano for the first time. (source)

mouseover text: Saying ‘what kind of an idiot doesn’t know about the Yellowstone supervolcano’ is so much more boring than telling someone about the Yellowstone supervolcano for the first time. (source)

Once I was thinking in this direction, I was back in my “normal” operating mode - I like to share everything I can about what I’m learning, knowng that someone else out there might find value in it. I often share very basic things, because they either are not basic to me, or if they are basic to me, I still didn’t learn about them until “recently”, and it might be my day to learn the obvious thing.

So, I embraced being the least experienced developer in the room, and suddenly had a topic to talk about.

It’s possible to plan for not knowing where you’re going #

The part of me that wants to pass himself off as cool, calm, collected, professional, and knowledgeable is reluctant to write this part…

For both talks, I didn’t know precisely what I wanted to say, but I had a rough idea. So I started making slides, and adding full sentences and paragraphs of text to them (shudder). As I needed screenshots and code snippets, I grabbed them and added them.

I kept bouncing between content as it existed in my head and the content as it existed on the slides, and slowly nailed down a coherent narrative.

The slides #

I used Keynote, and never considered doing any live coding. It often doesn’t go well, and I didn’t want to have to be improvising even more on the fly than I would be.

So, I made heavy use of screenshots and gifs, and weaved them into a slide deck.

I started with paper notes I put together on the talks I was giving. They were haphazardly organized, but I dutifully transcribed everything into a slide.

I wrote out “whole sentences” on slides, sometimes paragraphs. I was working in the direction of creating that great faux pas, of reading my slides to the audience.

I shuffled slides around, added sentences/bullet-points where needed, often giving the talk in small chunks “in my head”, and making adjustments as I went.

Once I had a basic “flow” down, I pulled the sentences out of the slide and copied into the presenter notes below the slide, and dropped a few related words into the content of the slide.

The few words would be enough to remind me what I wanted to talk about, and I could reference the presenter notes if needed, and now, without my narration, the meaning of each slide wasn’t obvious when it popped up.

The results #

I gave two talks! I recorded both talks on my cell phone, so I could figure out how to improve them. I made a landing page for both talks, because it takes no effort to do so.

Here’s both of those pages, with links for slides and the recordings themselves:

I gained a lot from both of these talks. The talk at Boulder Ruby Group was particularly instructive, as everyone in the room was quite knowledgable, and the “talk” unfolded as more of a dialog than a standard one-way presentation.